Predators:

Tundra Swans have few natural enemies other than humans. Little information is available in the literature regarding predation on tundra swans. Bellrose reported that nests have been destroyed by gulls (Larus spp.) foxes, jaegers, and wolves. The following species also occur in tundra swan habitat and could potentially prey on tundra swans: coyotes (Canis lutrans), river otters (Lutra canadensis), minks (Mustela vison), black bears (Ursus americanus), grizzly bears (U. arctos), Golden Eagles, Bald Eagles (Haliaetus leucocephalus), mountain lions (Felis concolor), skunks (Mephitis spp. and Spilogale spp.), and raccoons (Procyon lotor). These species no doubt take some toll of eggs and young on the tundra, but their influence on the swan population as a whole is very small. An aroused adult Tundra Swan is quite a formidable opponent, and a pair can usually fend off most predators.

During migration and on the wintering grounds, the Tundra Swan has been protected traditionally by bans on hunting. This is partly because there is broad public sentiment for protection of such aesthetically pleasing creatures. There is now a limited open season in some western states, however, with pressure to extend the season to other areas.

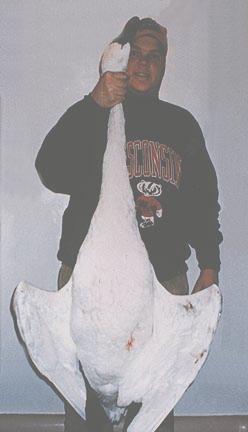

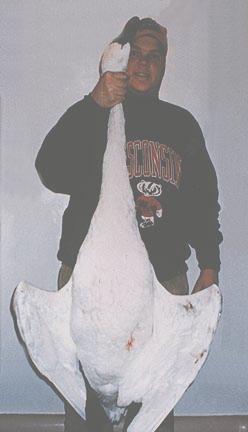

In a few states, experimental hunting of Tundra swans is allowed. Generally, a one swan per hunter limit is imposed. The Tundra swan is one of North Dakota's "special" waterfowl. Properly cooked the "breast straps" of a swan are not unlike large strips of filet mignon and about equal in flavor and tenderness. The bird makes an arresting mount whether in your den or your favorite bar. Swans are wet feeders and cannot be decoyed into the grain fields. Hunting is almost entirely done by scouting and pass shooting.

Examples of Tundra Swan Hunting Violations:

During the 1995 hunt, the Refuge staff noticed numerous violations that tainted the shining example of high quality, fair pursuit, sportsman-like conduct that migratory bird hunters at Bear River Refuge have exhibited in past years.

Skybusting, which is the practice of shooting at high flying birds, was observed many times last year, said Al Trout, Bear River s Refuge Manager. This indiscriminate shooting ends up crippling a large number of birds, rather than the intended outcome that all sportsmen strive to achieve, which is that of clean, direct kills, with no unnecessary waste, Trout added. In addition to skybusting, shooting from the main dike road, party hunting and hunting without a permit were cited. It was believed that unless all of these issues were quickly addressed, the reputation that had gained Utah s Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge its place as one of the premier waterfowl hunting areas in the United States could be destroyed.

In considering how to once again make hunting at Bear River Refuge a quality experience, several alternatives were considered. It was the goal of those responsible for the refuge hunting program to not only address and solve these most recent problems, but to do so with as little impact as possible to the majority of hunters who observe the basic ethics practiced by sportsmen in Utah. After careful consideration, the following refuge-specific regulations were submitted for the 1996 hunting season. These regulations are in effect only on the Refuge, and do not pertain to statewide regulations.

1. No hunting or shooting is permitted within 100 yards of principal refuge roads (the tour road).

2. While in the field, hunters shall possess and use only nontoxic shot.

3. Use of pit or permanent blinds is not permitted.

4. The Refuge, including parking sites, is closed 2 hours after sunset (end of shooting hours). Decoys, boats, vehicles and other personal property may not be left on the Refuge overnight.

5. Parking is permitted in designated parking sites only.

6. Hunters who take or attempt to take tundra swans must possess a Utah State 7. Swan Permit and may not possess or use more than 10 shells per day while hunting swans.

8. Any person entering, using or occupying the Refuge for waterfowl hunting must abide by all the terms and conditions in the Refuge hunting brochure.

Taking of tundra swan eggs and the hunting of flightless molting birds by Native Americans are significant mortality factors in some areas.

Examples of Hunting Historical Accounts:

Wheaton 1882: Not common, spring and fall migrant, perhaps also winter resident. Most numerous on Lake Erie than elsewhere, though occurring generally throughout the State. Mr. Langdon gives it as a rare migrant. In March 1877, I saw several specimens from Western Ohio, and the Scioto and Muskingum River.

Jones 1903: During the spring 1899 this swan was numerous in Lorain county where many were killed by hunters. It is a rare migrant in the state, seldom in its passage unless stopped by stormy weather.

Hicks 1935: Trautman and Trautman 1968 : Largest flights occur along south shore of Lake Erie, usually during or preceeding full moon.

During the early 20th century,

The number of Whistling Swans has decreased considerably since the turn of the century, though not as drastically as the Trumpeter. The swan feathers were a fashionable accent for women's clothing, especially hats. Many died from the poisonous lead shot of hunters that they ingested with their food. They often seek safety in the federally protected refuges along the Carolina coasts.

Management Consideration:

The tundra swan is the most common and widespread swan in North America. Winter surveys of tundra swans during the 1950's in the United States revealed an average population of 78,000. This figure increased to 98,000 during the 1960's and to 133,000 during 1970-74. The lowest population recorded from 1949 to 1974 was in 1950 at 49,000, and the highest was 157,000 in January 1971. Although the number of tundra swans found on the winter surveys has varied considerably from year to year, there has been a slow increase in the continental population over the last 25 years.

The principal factor limiting Tundra Swan populations is the adverse weather the swans often face on all parts of their range, but particularly on the breeding grounds. A late spring may prevent nesting; an early freeze-up may cause heavy casualties among the young. Consequently, the size of wintering populations may swing widely, with the number of young birds varying from less than 10 per cent to more than 30 per cent of the total. The western population is exposed to a somewhat less severe climate in both the breeding and wintering ranges; this may explain why, although the range of the western group is smaller, the two populations are roughly the same size.

Another factor now threatens the future of the Tundra Swan. Swan migration and winter habitats are being altered by human activity. Water pollution in Chesapeake Bay and the lower Great Lakes and water diversion east of the Rockies may reduce food supplies on the wintering grounds. Drainage of sloughs on the prairies and changing water levels and flow rates due to dam construction and water diversion endanger all the major staging areas.

The change in the feeding habits of Tundra Swans poses an important question. Are the birds switching from aquatic plants to field grains because they prefer this newly discovered food source, or is the destruction and pollution of many marsh areas forcing them to find other food sources? In either case, their increasing dependence on agricultural crops leaves them vulnerable to sudden changes in crop production.

Tundra Swans are rugged, long-lived, durable birds accustomed to adversity. However, they tread an ecological tightrope; the advantages provided by isolated breeding grounds are offset by a long migration route and a short breeding season. Human developmental activities now extend throughout the swan’s range and may very well determine the fate of this magnificent bird.