This story is loosely based on a small late Paleo-Indian site I excavated in the Thunder Bay area. Although the site now lies many hundreds of feet above the current lake shore, at the time it was occupied the waters of glacial Lake Minong lapped its margins...

It was a long wait. Everyone was hungry now; skin drawn tight over lean frames, thick caribou skin clothing barely keeping out the autumn chill. Three weeks had passed since they had arrived at the crossing but no animals had been seen. Their supplies of dried meat were dwindling and the few fish they had been able to spear in the river shallows didn't go far among fifteen people. For years they had been coming to the same place, timing their visits to coincide with the dispersal of the caribou from their calving grounds to the winter feeding areas. For years their timing had been right, but this year something was wrong. Meahnung sniffed the air cautiously, trying to catch a scent of caribou musk or a faint hint of crushed grasses. Nothing. The sweet smell of the first decaying leaves and the ever present dampness of the lake crowded his nostrils. The first frosts had begun to hasten the world towards winter. For the last three mornings tiny splash pools back from the lakes shore had been glazed with ice.

From his vantage point on the high sandy peninsula he could see for miles down the lakes shore. If any caribou were moving down there he would be able to see them, and if they unexpectedly chose to follow the crest, he would see that too. But still he fretted, constantly turning his eyes along the shore in case he missed their passing. Others from the camp had abandoned their stations to forage inland in the hope of cutting off a group of stragglers, or finding something else to satisfy their hunger. Meahnung stayed at the lake shore watchful, silent and dismayed.

Three more days passed. Old woman Toowook died in her sleep; her stiff body was found in the morning curled up like a child's in her nest of furs. With a feeling of hopelessness the men made a pile of dry brush and placed the old woman with her few precious belongings on the heap. A spark was struck into some bone-dry grass. It caught, was thrust under the brush pile and within seconds the flames leaped up among the dry branches, spitting sparks and flames as the fire reached towards the old woman's body. A tongue of flame lashed the dry fur she was wrapped in and the acrid smell of burning hair blended with the smoke. Soon the corpse was engulfed in fire. The people encircled the pyre, keening or standing in silent contemplation, their thoughts averted from their present plight as they watched the flames rising higher. Gradually the heat of the fire subsided. In the centre the old woman's form could still be made out, dripping and crackling as the last remnants of her parched shell were rendered by the flames. In the morning Toowook's daughter would rake around in the ashes picking out the last remaining parts of her mother's body, to be buried away from the camp, overlooking the lake.

With nothing else to do now that the momentary diversion of the cremation was over, Meahnung resumed his position on the peninsula. He squatted, swaying back and forward on his heels, his arms clamped tightly around his knees in his customary waiting position. He sat there for many days, deep within himself. Only his eyes, which constantly combed the land showed that he was still alert.

A raven flew across the sky to the west, barrel rolled then dived out of site into the tops of the trees. Meahnung followed it with his eyes then suddenly noticed something moving along the shore about a mile from his lookout. At first he thought the dark shape was a bear, but as he continued to watch more dark shapes emerged from the cover of the cedars and began to move along the shore. Keeping himself well hidden he slid behind the rocks and, once out of sight, raced back to the camping place. Two of the men were out looking for small game, but there were enough. Picking up their short spears they raced downwind to where the river joined the lake. For years they had attacked the caribou as they massed at the water's edge. The first animals to arrive were always reluctant to cross the wide river until the press of those behind forced them in. If the hunters timed their attack well, they could sandwich their indecisive prey between themselves and the water, killing a good number of them before those nearest the water plunged in. Timing was crucial. If the herd became spooked too early they would disperse before the crossing. If the hunters were too late in attacking many would escape into the water. As Meahnung watched the animals massing along the shore he felt a stir of excitement tinged with relief. The caribou looked sleek and well fed from their summer grazing. There would be rejoicing and feasting in the camp tonight, and Meahnung would be sure to leave an offering for his guide and helper, the raven.

THE ARCHAIC PERIOD: 6,000 - 200 B.C.

During an archaeological survey of the Mississagi River, we found a number of Archaic period campsites where the tool-stone of choice was the grey cherts from the Lake Huron islands. Since this material was not available locally, I have speculated that the people travelled down to the big lake to trade and to help provision themselves for the coming winter. But travelling downstream is relatively easy - travelling upstream is an entirely different matter...

The roar of the rushing water and the hammering of the peoples pulses in their eardrums made communication by any other means than signs, impossible. The heavy dugout was poised precariously at the apex of the rapid; its prow carving deeply into the smooth water at the top of the vee, its stern moving slowly from side to side in the first standing waves. All hands were clinging to the taut woven rope which connected the canoe to the people on the shore. Blackflies hovered around their eyes as they strained to haul the canoe over the brink. They had no time to brush the flies away or to wipe the sweat from their streaming faces. Every ounce of strength was required to line up this, the last rapid of the day. Slowly the prow lifted over the lip of the vee and surged into the quieter water above. The two adults and four children breathed a sigh of relief as they pulled the canoe in to shore and secured it to a tree root on the bank.

The previous year they had lost many of their prized possessions and a sizable bundle of dried fish when their canoe had been forced sideways and tipped in exactly the same spot. What little advantage they had gained over the summer from their fishing amongst the islands on the big lake had been lost. The fine fat lake trout they had carefully dried in the sun, floated off down the river,

and the precious light grey chert they had bought at the expense of many fine skins dropped to the bottom of the boiling waters. This year they were more lucky, although their successful lining of the rapids was due as much to skill and

teamwork, as luck. Their combined efforts had brought them safely through to an area of winding channels, swamps and thick bush where moose and bear were plentiful. There, once winter took hold they would be able to set up a stable winter camp until the seasons changed again and it was time to move on.

That evening they pulled the canoe ashore at a wide beach just below an open gravel terrace. They had camped there many times before. Their old fire pit was still visible beneath the new grass and a canoe which had finally succumbed to decay lay rotting beneath the tall pines where they had left it. As the family erected their portable shelter of spruce boughs and skins, and started a fire, the man selected a number of willow saplings from along the river bank and brought them back to the camp. Sitting cross legged in the warmth of the blazing driftwood he split the bark from the stem, using a razor sharp flake of chert, and carefully removed the inner bark from each piece. Once he had accumulated a sizable pile of fibres he began to twist them between his hands, spinning out a thread of uniform thickness and great strength. Another few weeks and he would be stalking the wary moose in waist deep snow and attacking the bear in his den. Those would be their mainstay through the long winter months. But now he had to prepare. If something went wrong and his hunting was unsuccessful he had to have something to fall back on. Starvation and death could come quickly in the bitter cold.

He had noticed some droppings on the portage showing that the hares would be common this year. With some cunningly placed snares made from the strong cords he could keep his family from starving with hare meat if all else failed. His family could set and maintain the snares while he was away hunting. Although the lean meat provided is difficult to survive on because of the lack of body fat, they would provide a source of sustenance until he could return with something more satisfactory.

He looked up from his work and gazed into the fire. Some nice fat bear in their dens would be best, he thought. He would find them by the tell tale yellow tinged air vents their breath melted through the snow. Killing them was a dangerous business, but it was worth the risk. A couple nice fat bear, some beaver and a few moose would see them safely through until the ice began to melt and the sap began to run.

As the smoke from the campfire settled and spread along the surface of the water, and dusk descended on the river the family moved closer to the fire. The man continued to strip and twist the willow fibres, now with the help of his two eldest children. The two youngest, seemingly oblivious to the chill in the autumn air played in the loose gravel by the river's edge while the woman patched sections of moosehide together with a bone needle and sinew. Her thoughts too were on the coming winter. She wondered if she would lose more of her children this year to the bitter cold.

THE MIDDLE WOODLAND PERIOD: 200 B.C. - A.D. 1000

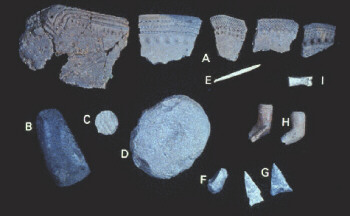

Although much of the pottery archaeologists find on Woodland sites in Ontario is skillfully made, every so often, we find pieces which have clearly been made with inexperienced hands. In this story I have tried to zoom in on one small incident in the life of one small girl, as the art of making pots is transferred from one generation to the next...

Her fingers were aching and swollen as the old woman pulled a handful of cold clay from the large pot and started to knead it. The little girl by her side watched as she worked the clay until it was soft and pliable, rolling it carefully between her hands into long thin flexible strips which she carefully laid on a piece of birchbark.

The little girl dipped her hand into the large pot and pulled off a fist sized chunk of clay. Working intently, she kneaded the clay as she had seen her Grandmother do. Within a few minutes another group of clay strips were lying on the birchbark.

The old woman had built up the sides of the vessel and was now working on the neck. By changing the diameter of the coils she lay, one on top of the next, she first constricted the neck, then widened it to flare out at the lip. She smeared each strip into the next with a deer rib so that the clay melded to form a cohesive whole. Once the basic shape was completed, she smoothed its inner and outer surfaces with a damp piece of leather until it was almost impossible to tell where the coils of clay had been laid. The cold clay felt soothing to her hands. It seemed to ease away some of the pain and inflammation.

She looked over at her granddaughter and vividly remembered sitting at her own grandmother's side learning how to mold the clay. How long ago had that been? So many seasons had come and gone. So many people she had known and loved had died. Yet as she watched the little girl moulding the clay strips in her inexperienced hands she recalled the loving patience her own grandmother had shown when, as a little girl, she had pulled some clay from the pot and tried to copy her.

Back in those days the sun had been warmer, it seemed, and her father had always managed to bring back something for them to eat. She could not remember ever being cold. Nowadays her old body only felt comfortable on the warmest days and she constantly fretted that the hunting would be bad or that the fish run would be late. Back in those days life had been one long summer of games and joy, of chasing dogs and splashing along the lake shore, of hunting frogs in marshes and of picking berries. She hardly remembered the winters at all. Now summer was a fleeting time, punctuating the long cold darkness of winter.

Her granddaughter began to add the strips of clay to her tiny misshapen base. Her clay kept changing shape in her hands as she held it too tightly, and she had to keep pressing it back so that it still resembled a pot. Her tongue was pressed tight into the corner of her mouth in concentration.

'Look Grandma' she said, 'mine's so small and ugly, we should throw it away!'. The old woman looked at her, remembering when she had felt the same way, all those years ago. She petted the girl on the head and picking up her pot told her that it was much better than she had managed when she was a girl.

'We could throw it away, but if we do that you won't need the tool I made for you to decorate it with. And I think your mother is looking forward to that present you promised her.'

The little girls face lit up as the woman passed her the small serrated stone tool. She had carefully notched both of its edges so that if you used it one way it left a series of notches in the clay, and if you used the other side, it left a sinuous mark like the side of a clam shell.

'Let's see how beautiful your pot looks after we have decorated it. I bet it will be the nicest your mother has ever seen.'

During the next hour the old woman slowly guided her granddaughter as they applied their pottery tools to the soft clay. She showed her how to arrange rows and lines of decoration to give a pleasing pattern of zones, and showed her how to use the end of a twig to push the clay from the inside to form bosses around the pots neck. By the time they had finished both were highly satisfied with their work. The process of decorating the little pot had helped to push it back into shape, so that when the old woman laid it gently down it looked like a minature of her own.

A few days later the old woman left her seat by the lake shore and collected the pots from where she had left them to dry in safety. The little girl was playing with her friends down at the water, but when she called her the girl lost all thoughts of play.

The old woman started to prepare a fire. She chose twigs and branches carefully and placed them on the dry sand in a special order so that when the pots were laid in the fire the temperature would be just right to fire the clay without cracking it. There will be time enough to teach her this another day, she thought.

After all the pots were safely positioned in the fire they covered them over with a matt of small twigs. The grandmother explained that the wood she had used would smoulder for a long time so that the pots would not crack or split, as they would in a racing hot fire.

'Now, you go and get some embers from the cooking fire and we will light it.'

The little girl scampered over to the fire, pulled out a burning branch and hurried back to her grandmother.

'Now, light it low down on the sides so that it burns from the bottom up.'

The girl did as she was told, and soon a plume of smoke was curling up through the heap of twigs, crackling in the drier branches.

'Well, my little one, lets get something to eat while the fire does its work. There's nothing more for us to do until the embers are cool.'

The fire burned long into the night and continued to smoulder long after the people had gone to sleep. Like many older people, the woman did not linger long in sleep, and was raking the ashes away from the pots before the little girl had awoken. Despite her efforts to control the heat, two of her pots had cracked. Never mind, she though, we can use them for storage until they break.

The little girls pot, being the smallest had sunk into the ashes and was nearly concealed. Gently the old woman pulled it free and inspected it. Parts of its surface had turned a fine reddish brown. She blew the remaining ashes out of the shallow depressions of the decoration and turned the vessel appaisingly in her hands. One day soon, she thought, this little girl will be crafting perfect pots for her own family.

Back in the lodge the little girl was just waking as her grandmother entered. 'Did it work Grandma?' she asked excitedly. The old woman didn't answer, but she smiled as she held out the still warm pot for her to inspect.

THE LATE WOODLAND PERIOD: 700 A.D. - 1650 A.D.

From time to time, all of us yearn for something different in our lives. In this story, which is set at a major fishing village on an island in the river at Sault Ste. Marie, I have described one persons longing to see something beyond the world into which she was born. We know from the archaeological evidence that peaceful trading must have occurred between neighboring peoples on a regular basis. Perhaps, sometimes, more than just furs and food were exchanged....

She looked at the old, giggling women as they worked. Each one had been a beauty once, hiding their shy smiles from the admiring glances of the young men. Now they had their families and their endless chores. From sunrise to sunset they chopped wood, cleaned nets, looked after their numerous children and performed a hundred other duties their men expected of them. In return what did they receive? More jobs, more work. If they were lucky, a word of appreciation or a tender gesture.

She watched the older women softening the leather by chewing on it, hour after hour, their teeth becoming worn down, sore and useless stumps and their mouths dry and painful in the service of their families. She had noticed the quick transition from attractive young woman to unappealing drudge, as each of her older friends gave up the delights of childhood and took on the role expected of her. She was determined to do something different.

From the snatches of conversation she had heard, she gathered that a large party of Huron traders was expected to arrive within a few hours. She had seen them many times before, when they came to exchange their sweet ripe corn and pots full of fleshy beans, for the furs, copper and birch bark her people took from the woods. The Huron were strange looking people, fierce and haughty. Their language was different to hers, but like many of her people, she had learned to understand many of their words; enough at least to know that they thought highly of themselves and looked down on her people. Her villagers, in turn, laughed at them behind their backs, calling them women, for spending so much time planting the land instead of hunting, like real men.

Although many in her village despised the Huron for their arrogance, she had noticed that it had become quite fashionable for the young men to cut their hair in the Huron fashion, and that many of the women were copying the trader's pottery in their own local clays.

Some of the men from the village had travelled south with their trading partners and had returned telling stories of huge villages enclosed by walls of log; of massive lodges stretching the length of her village, and of vast hilltops of waving corn. She found it hard to picture these things, having never travelled from her father's hunting territory, but the idea of such riches fascinated her. Somehow, she thought, I will find a way to see these things for myself. Then, if I grow fat, ugly and toothless like these old women, I will at least have some memories to dream of.

Full darkness had barely descended when the Huron arrived. Their sleek canoes, acquired from the Nipissings the previous year, were painted with designs, unintelligable to her and strangely menacing. As they beached the canoes, a cry of welcome rose above the constant noise of the nearby rapids. The Huron traders, all men in their early twenties, stepped proudly ashore and walked between the eager faces of the assembled people. There would be time enough for trading. Tonight was the time for re-establishing ties and for relaxation after their long journey. The goods would be respectfully ignored until the serious negotiations started in the morning.

The girl had rushed to the shore with the rest of the women to watch the arrival of the strangers. The young Huron paid no attention to the crowd, but walked over to the central fire and quietly seated themselves close to the village elders. Although she felt sure that their curiousity was as keen as her own, nothing in their faces or behaviour betrayed it as they stared silently into the fire. After a while, one of the men reached into a soft leather pouch and pulled out a pipe. In the glow of the fire she could make out the shape of a wolf's muzzle on it's bowl. The man filled it with tobacco from his pouch, lit it with a twig from the fire and drew in a long draft of smoke. This seemed to break the tension, for within a few minutes all the men were smoking and some were beginning to talk quietly with the men from her village.

She had been watching one of the traders especially closely. He was a tall, straight man, with a large hooked nose which gave him a look of great ferocity. She had been surprised to find him looking straight at her, which had made her feel quite nervous. Shortly thereafter she had left the main fire and returned to the women's area to resume cleaning nets. Within a few minutes she had lost herself in the work and the chatter of her companions.

Some time passed before she noticed that the women's conversation had ceased. She could hear the crackling of the flames and the low sounds of men talking above the ever present sound of the rapids. The tall Huron was standing on the far side of the fire, staring at her. In the wavering shadows he looked strange and dangerous and she was frightened under his gaze. The he smiled. It was as if the sun had suddenly come out from behind a thundercloud. His fierce and alien face was split by a wide, handsome grin, showing a broad expanse of straight, clean teeth. In that instant, she ceased to see him as a dangerous and unpredictable outsider. Here before her was a handsome young man at whom, to her surprise, she found herself smiling happily back. Ignoring the whispers and lewd comments of the other women, he walked over to her and stretched out his hand. She took it, and together they walked away from the fire, and the raucous laughter of the women.

Perhaps, she thought, I will see those fields of corn, those huge villages, and build myself some dreams for my old age after all.

LEGEND OF SIX NATIONS .. Iroquois

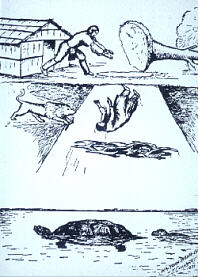

Long, long ago, in the great past, there were no people on the earth. All of it was covered by deep water. Birds, flying, filled the air, and many huge monsters possessed the waters.

One day the birds saw a beautiful woman falling from the sky. Immediately the huge ducks held a council.

How can we prevent her from falling into the water? they asked.

After some discussion, they decided to spread out their wings and thus break the force of her fall. Each duck spread out its wings until it touched the wings of other ducks. So the beautiful woman reached them safely.

Then the monsters of the deep held a council, to decide how they could protect the beautiful being from the terror of the waters. One after another, the monsters decided that they were not able to protect her, that only Giant Tortoise was big enough to bear her weight. He volunteered, and she was gently placed upon his back. Giant Tortoise magically increased in size and soon became a large island.

After a time, the Celestial Woman gave birth to twin boys. One of them was the Spirit of Good. He made all the good things on the earth and caused the corn, the fruits, and the tobacco to grow.

The other twin was the Spirit of Evil. He created the weeds and also the worms and the bugs and all the other creatures that do evil to the good animals and birds.

All the time, Giant Tortoise continued to stretch himself. And so the world became larger and larger. Sometimes Giant Tortoise moved himself in such a way as to make the earth quake.

After many, many years had passed by, the Sky-Holder, whom Indians called Ta-rhu-hia-wah-ku, decided to create some people. He wanted them to surpass all others in beauty, strength, and bravery. So from the bosom of the island where they had been living on moles, the Sky-Holder brought forth six pairs of people.

The first pair were left near a great river, now called the Mohawk. So they are called the Mohawk Indians. The second pair were told to move their home beside a large stone. Their descendants have been called the Oneidas. Many of them lived on the south side of Oneida Lake and others in the valleys of Oneida Creek. A third pair were left on a high hill and have always been called the Onondagas.

The fourth pair became the parents of the Cayugas, and the fifth pair the parents of the Senecas. Both were placed in some part of what is now known as the State of New York. But the Tuscaroras were taken up the Roanoke River into what is now known as North Carolina. There the Sky-Holder made his home while he taught these people and their descendants many useful arts and crafts.

The Tuscaroras claim that his presence with them made them superior to the other Iroquois nations. But each of the other five will tell you, Ours was the favoured tribe with whom Sky-Holder made his home while he was on the earth.

The Onondagas say, we have the council fire. That means that we are the chosen people.

As the years passed by, the numerous Iroquois Families became scattered over the state, and also in what is now Pennsylvania, the middle west and southeastern Canada. Some lived in areas where bear was their principal game. So these people were called the Bear Clan. Others lived where beavers were plentiful. So they were called the Beaver Clan. For similar reasons, the Deer, Wolf, Snipe and Tortoise clans received their names.

Long ago when the word was sound, an old Lakota spiritual leader was on a high mountain and had a vision. In his vision, Iktomi, the great trickster and searcher of wisdom, appeared in the form of a spider. Iktomi spoke to him in a sacred language. As he spoke, Iktomi the spider picked up the elder's willow hoop which had feathers, horsehair, beads and offerings on it, and began to spin a web. He spoke to the elder about the cycles of life, how we begin our lives as infants, move on through childhood and on to adulthood. Finally we go to old age where we must be taken care of as infants, completing the cycle.

But, Iktomi said as he continued to spin his web, in each time of life there are many forces, some good and some bad. If you listen to the good forces, they will steer you in the right direction. But, if you listen to the bad forces, they'll steer you in the wrong direction and may hurt you. So these forces can help, or can interfere with the harmony of Nature. While the spider spoke, he continued to weave his web.

When Iktomi finished speaking, he gave the elder the web and said, The web is a perfect circle with a hole in the center. Use the web to help your people reach their goals, making good use of their ideas, dreams and visions. If you believe in the great spirit, the web will catch your good ideas and the bad ones will go through the hole.

The elder passed on his vision onto the people and now many Indian people have a dream catcher above their bed to sift their dreams and visions. The good is captured in the web of life and carried with the people, but the evil in their dreams drops through the hole in the web and are no longer a part of their lives. It is said the dream catcher holds the destiny of the future.

Legend of Ojibwe Dream Catcher

Long ago in the ancient world of the Ojibwe Nation, the Clans were all located in one general area of that place known as Turtle Island. This is the way that the old Ojibwe storytellers say how Asibikaashi (Spider Woman) helped Wanabozhoo bring giizis (sun) back to the people. To this day, Asibikaashi will build her special lodge before dawn. If you are awake at dawn, as you should be, look for her lodge and you will see this miracle of how she captured the sunrise as the light sparkles on the dew which is gathered there.

Asibikaasi took care of her children, the people of the land, and she continues to do so to this day. When the Ojibwe Nation dispersed to the four corners of North America, to fill a prophecy, Asibikaashi had a difficult time making her journey to all those cradle boards, so the mothers, sisters, & Nokomis (grandmothers) took up the practice of weaving the magical webs for the new babies using willow hoops and sinew or cordage made from plants. It is in the shape of a circle to represent how giizis travels each day across the sky. The dream catcher will filter out all the bad bawedjigewin (dreams) & allow only good thoughts to enter into our minds when we are just abinooji. You will see a small hole in the center of each dream catcher where those good bawadjige may come through. With the first rays of sunlight, the bad dreams would perish. When we see little asibikaashi, we should not fear her, but instead respect and protect her. In honor of their origin, the number of points where the web connected to the hoop numbered 8 for Spider Woman's eight legs or 7 for the Seven Prophecies.

It was traditional to put a feather in the center of the dream catcher; it means breath, or air. It is essential for life. A baby watching the air playing with the feather on her cradleboard was entertained while also being given a lesson on the importance of good air. This lesson comes forward in the way that the feather of the owl is kept for wisdom (a woman's feather) & the eagle feather is kept for courage (a man's feather). This is not to say that the use of each is restricted by gender, but that to use the feather each is aware of the gender properties she/he is invoking. (Indian people, in general, are very specific about gender roles and identity.) The use of gem stones, as we do in the ones we make for sale, is not something that was done by the old ones. Government laws have forbidden the sale of feathers from our sacred birds, so using four gem stones, to represent the four directions, and the stones used by western nations were substituted by us. The woven dream catchers of adults do not use feathers.

Dream catchers made of willow and sinew are for children, and they are not meant to last. Eventually the willow dries out and the tension of the sinew collapses the dream catcher. That's supposed to happen. It belies the temporary-ness of youth. Adults should use dream catchers of woven fiber which is made up to reflect their adult "dreams." It is also customary in many parts of Canada and the Northeastern U.S. to have the dream catchers be a tear-drop/snow shoe shape.

The moccasin was made out of buckskin and decorated with porcupine quills. One of the native legends says that the first pair of moccasins, were made for a great chief of the Plans; who had tender feet.

His medicine man came up with the first pair moccasins; which were made out of elk hide; after the chief had sentenced him to death on the day when the moon was round, if he ( the medicine man ) didn't Cover The Earth With Leather as the tender footed chief had ordered.

An Ojibway Legend tells of a little Ojibway girl lost outside during a bitterly cold winter. Searchers found a Lady Slipper blooming in the snow, where the little girl was last seen. Thus the Lady Slipper became the model for the Ojibway Moccasin.