THE LONG POINT COMPANY

Harry Barrett's Lore & Legends

Photo Courtesy of Dave Stone

Photo courtesy of Richard Goodlet

Photo Courtesy of Joan Wamsley Barrett

Photo courtesy of Harry B. Barrett

Photo courtesy of Harry B. Barrett

From Crown Land to Private Ownership

In the late 186Os the great sand spit of Long Point underwent a legal change with far-reaching consequences. Until then most of it was open crown land; now the larger part became the private property of a group of sportsmen - businessmen chartered as the Long Point Company. Although at various times since its formation the Company has been accused (perhaps with some truth) of being a monopoly by which rich men have deprived others of access to the bounty of nature, it has also saved that bounty. Today, over one hundred years after the Company took over, Long Point, which could easily have met the sad fate suffered by other ecologically fragile enclaves, is one of the best-run private preserves in Canada.

Around the middle of the nineteenth century, Long Point was indeed endangered by licentious pleasure-seekers, by over-eager lumbermen, and by market hunters.

Accessible to, but still separated from, the growing settlements on both sides of the lake, the Point developed an unenviable reputation for drunken-ness, murder, and debauchery of every kind. So-called hotels appeared, and wild, but all too accurate, tales began to reach the mainland. Gamblers and others wishing to indulge in activities now being regulated by the laws of both the American and Canadian governments could readily reach the Point by steamboat or sailing schooner hired from Buffalo or Erie. Few officials followed them or could prove the lawbreaking if they did. For a brief period Courtright Ridge supported a full-fledged brothel, its "ladies" having been transported there by steamer from Buffalo.

According to Edward Harris, the situation soon reached the point where:

• Rev. Dr. Ryerson, Chief Superintendent of Education in Ontario, who had shot there from boyhood, wrote the Government that it was then impossible for the respectable man to go there, and ruin for any young man to shoot there. That immorality, drunkenness and a low tone was prevalent throughout the place.

As Ryerson's complaint suggests, this was the period during which hunt-ing for sport became very popular among the rising upper and middle classes on both sides of the lake. But it was also the period during which market hunters invaded Long Point. Until the early 1850s the ducks and game in the outer marshes had been relatively free of molestation. The lust of professional trappers and hunters for cash and/or liquor had been satisfied by the pelts and game birds taken from the more easily accessible marshes on the mainland, notably around Big Creek and Turkey Point. Market hunters satisfied their needs there, too, as the new Canadian cities demanded only a small amount of wild game. And the local farmers, to the amazement of many travelers in Upper Canada in the nineteenth century, preferred salt pork and sour bread, varied occasionally by home-grown beef and poultry, to fish, water fowl, and other game.

But as the cities grew in size, so did the demand for wild fowl, particularly at the border points, since American supplies were generally less plentiful. Once the Grand Trunk Railway opened in 1856, Lake Erie's north shore came under tremendous pressure to supply that demand.

Each spring local hunters lined the lake banks to knock down the myriad's of passenger pigeons as they swept in low over the water, rising only suffi-ciently to clear the shore as their migratory urge drove them inland to their vast nesting grounds. Countless thousands more were smoked, netted, or jack-lighted from their roosting sites. Finally, further onslaughts were made on the succulent squabs.

Though much more wary than the passenger pigeons, ruffed grouse, quail, and wild turkey were similarly slaughtered.

The government provided little protection. So the ruthless slaughter spread from the lakes of eastern Ontario to the great duck marshes of the St. Clair flats and Mitchell Bay. As they became rapidly depleted, those of Big Creek and Turkey Point, though farther from market, looked more lucrative. They soon suffered a similar fate.

Then all eyes (and guns) turned to the last remaining incubator for wild-duck in southern Ontario the great marshes of Long Point beyond the Cut. The market hunters, with no thought for preservation or conservation of this great resource, moved in from both sides of the lake, taking a tremen-dous toll each spring and fall as migrating waterfowl attempted to settle in to rest and feed. Nor did summer bring any respite for them or for the muskrat and deer that lived in the marshes and ridges running from the spine of the south beach.

The depletion of wildlife was accompanied by a depletion of tree cover, and consequently of the land itself. Increased (mostly illegal) lumbering denuded the ridges of their cover, and protection from wind and water was lost. Large areas of the always unstable Point began to succumb to the waves.

Complaints about the lumbering and the conduct of the professional market hunters and other unsavoury trespassers reached the government and finally became so embarrassing that it was forced to take some form of action. But what? Most of the Point was crown land, but attempts to police it by occasional patrols would be fruitless. Only a permanent, full-time force stationed on the Point could hope to bring it under control. Such an expenditure, for a next-to-worthless sand spit, would only bring the govern-ment under even more severe criticism.

The simplest solution appeared to be to sell it, and the Crown Lands Department was instructed to offer it for sale. Accordingly, surveyor James Black received instructions in February 1853 to: "Survey the outlines of the Point, and the limit between the dry land and the marshes or pools: also any islands adjacent, and prepare a plan, etc., with a view to the whole being disposed of at public auction."

This was not completed until 1857, but finally in that year sixteen blocks of land on the Point were advertised for sale at public auction. No bids were forthcoming. A second offer had the same result.

Photo courtesy of Norman Ferris

Early members of Long Point Company at The Cottages. From left , Lewis Cabot, John Manuel, G.H. Richards, Horatio Hathaway, M. Hewlett, J.I. McKenzie and J.T. Lord

About 1860 a group of Canadian businessmen from Hamilton and St. Catharines, with Colonel David Tisdale, a lawyer from Simcoe, to aid them, had constructed a punter's cabin and shanties near the Little Sandhills on the south beach of the Point. This was managed by Harry Woodward and soon became known as "Harry's Shanty". (Colonel Tisdale's garrulous uncle, Peter Price, held the Rice Bay section further west as his private property.)

The sports hunters who met at Harry's Place were among those who had become disturbed about conditions at The Point. At the suggestion of Tisdale, the government was persuaded to offer its lands there for sale once more, and several of the group from Harry's Place bid on them successfully.

On May 4, 1866, Block 1 to Block 16 a total of 14,934 acres was sold for a total of $8,540 to John Brown, George Hamilton Gillespie, Thomas Cockburn Kerr, William Little, David Tisdale, Laughlin McCallum, and Samuel DeVoe Woodruff.

The purchasers immediately petitioned the government for a charter of incorporation as "The Long Point Company" for those lands on the Point which they now owned and "are desirous of promoting for fishing and hunt-ing and otherwise to manage and make the land available for the purposes of the Company incorporated by this Act."

The charter was assented to by the Legislative Assembly on August 15, 1866. Of its eighteen clauses the following is of particular interest:

The Company may carry on the business of pursuing, protecting, and granting licenses to take game, muskrats, mink, otter, beaver, and fish, upon the said lands and property or in the water covering the same; and generally the doing of such other acts or things with the said land or with any mineral substance or thing, grown, or to be grown, found or being in or upon the same, as may promote the interests of the Com-pany, and not being contrary to the laws of this Province, or the terms of the Patent from the Crown.

The first meeting of the Company was held three days after its incorpora-tion. Kerr and Gillespie were elected president and secretary-treasurer respectively, and Tisdale was appointed solicitor. In addition, Charles Brown was appointed general manager (head keeper) at a salary "at the rate of six hundred dollars per annum by the month during pleasure", and William Leary was made his assistant.

Even at this initial meeting the founding members began to lay down rules of management which to this day have given the Company a good name with conservationists. From that time on, no spring duck hunting would be allowed and tall hunting would not commence before September. In season duck-shooting licenses would be required at $5 for one week or $8 for two. No trapping would be allowed in the fall, and trapping regulations were planned.

The Long Point Company was launched and soon would be a force to be reckoned with.

The Early Success of the Long Point Company

Painting photo courtesy of Harry B. Barrett

The Long Point Company came into being with its incorporation and the subsequent transfer to it of the crown lands which its founding members had purchased. Its goal of creating a stable environment in which members could enjoy pleasant interludes of sport hunting was not to be achieved immediately. There were many problems facing its first directors. The fragile environment had already been destroyed to some extent; it needed to be built up and would always require careful management. The poachers for which the Point had become a haven had to be won over or cleared out and there was no hope of achieving this until the Company gained control over all land on the Point and the goodwill of local residents who were accustomed to hunting and fishing there. Fishing rights (which the govern-ment had reserved) had to be obtained and administered. Stewards, game- keepers, and punters had to be hired and supervised. And, at the same time, the Company had to be managed to the satisfaction of all the members.

In the face of such demands, it was fortunate that the Company was made up of well-educated, tough, hard-headed businessmen who ruled with an iron hand, tempered with a spirit of fair play and respect for anyone with similar ideals, be he a corporation president or a local punter-guide.

The management of the marshlands of the Point began at the Company's first meeting with restrictions on hunting and trapping. These soon began to pay off in terms of the members' pleasure and in terms of cold cash, as well. By 1872 Secretary-Treasurer J.I. Mackenzie was able to say in a letter to the Commissioner of Crown Lands:

In the possession of this Company, Long Point is the only place in Ontario capable of being effectively protected for the preservation of game and of fur-bearing animals;... When the Company obtained Long Point, in 1866, the muskrats, mink and otter, were almost killed off by indiscriminate shooting and trapping; and although a rest was given for the season of 1867, the season of 1868 only produced some 3000 muskrat pelts, and nothing worth mentioning in other furs. Under the rules now in force, the catch this year of muskrats alone is 6,000.

Deer had completely disappeared from Long Point before the Company took it over. In 1890 a local hunter was to testify in a court case: "The last wild deer I know of on the Island [before the Company restocked it] were there when Henry Clark kept the lighthouse about 2 years before the Com-pany bought the Island [i.e., about 1864]." To re-establish a breeding herd, eleven deer were purchased for $50 apiece at Clearwater, Minnesota in February 1875. Within five years Company directors felt it was safe to allow very limited deer hunting to members only.

During the mid-1880s Walter Anderson, who owned land on the Point at Gravelly Bay but was not a Company member, also brought in four deer. The deer found today on Long Point appear to be the descendants of these two herds. From the records of several court cases in the early 1890s it is clear that the imported deer multiplied quickly in their new, marshy habitat.

Photo Courtesy of Lore and Legends

More important, stocks of water fowl were built up again, and members and their guests were soon taking very satisfactory bags.

Since the inception of the Long Point Company, the directors have adopted by-laws which reflected the wild life management principles being put forward by recognized authorities as the best at that time. Their self-imposed regulations incorporated practical conservation measures that were, until recently, far in advance of the game laws promoted by the prov-ince, and that even today are more restrictive.

To this day the hunting pressure on the waterfowl of the Long Point marshes has been much less than could have been maintained or enforced if they were under the control of the Ministry of Natural Resources or their various predecessors.

During periods of abundance, or if the numbers of a given species were particularly plentiful, the number of members and guests, as well as the daily bag and its species make-up could be altered to reflect this improved situation. If numbers warranted it, punters might be allowed hunting days after the members were through for the season. Alternatively, in poor seasons the rules could be tightened, even to the point of declaring a species completely off limits.

The Company's intention down through the years has been to maintain a productive wildlife habitat that is second to none on this continent, whether it be for deer, muskrats, waterfowl or shore birds.

The Company's first problem was that its purchases from the government did not include the entire Point. Some lots were already in private hands. Over the next few years the Company negotiated with the owners of these 2,000-odd acres. The Company or its founding members made purchases from Dr. Egerton Ryerson, who owned Ryerson's Island; Dr. James M. Salmon; Harry Clark, the former lighthouse keeper; Bernard Saunders; and John Spain. Ryerson was granted a life right to hunt over the Company marshes and to occupy the cabin he owned on his island; Dr. Salmon demanded and was granted life rights to hunt and fish over his former prop-erty and all the lands east of Spain's on Courtright Ridge, as well as permis-sion to build a lodge at The Bluffs or at Little Creek and to cut 4,500 cedar fence-posts in the next four years.

In addition to buying out other landholders, the Company was also faced with several outright squatters who had built shanties on the Point. Since these were all local residents whom the Company did not wish to antago-nize, there was no attempt at court proceedings. Quit-claim deeds were pur-chased instead from Edwin Finn, William Bantam, and Tisdale's uncle, Peter Price. Price was also granted a life right to hunt over the Rice Bay portion of the Company's holdings.

In total, expenditures for the extra land and the quit claims came to $11,136. By 1871 the Company controlled all sixteen blocks of land into which Long Point had been surveyed except Block H (196 acres), which had been reserved by the government for lighthouse purposes, and a quarter share (88 acres) of Block 2, which belonged to Walter Anderson, a lumberman of Normandale. At the time this arrangement appeared amicable enough, although there was to be bitter strife between Anderson and the Company later on. Relationships with the lighthouse keepers, on the other hand, remained excellent over the years. Many of the keepers were employed by the Com-pany to patrol the eastern end of the Company property.

Employing local trapper-poachers on the Point was one of the most astute moves the Company founders made. Gaining the confidence of such local men as William and Harry Woodward, William Leary, and Morris Fitz-morris, was a key step towards getting local cooperation with the Com-pany's regulations. Such cooperation was also achieved by explaining the common sense of the new regulations and by making it clear that there was plenty of employment, on fair terms, for those who would work diligently and honestly for the Company as keepers, punters, and trappers.

But neighbourhood cooperation was not complete and not enough. Out-right illegal poaching was common. And there was a loophole by which would-be poachers could gain easy and legal access to the boundaries of the Company's marshes. The problem was that James Black's original govern-ment survey of the Point had contained an error which deprived the Com-pany of about 475 acres of marsh north of Rice Bay and parts of the shoreline from Courtright Ridge to Ryerson's Island. Local hunters took advantage of this error, anchored their boats in this "no-man's land", and used them as headquarters for poaching along the western part of the big marsh.

The Company hired Thomas W. Walsh, P.L.S., to re-survey its land. When his report confirmed what the members had suspected, Colonel Tisdale wrote the Commissioner of Crown Lands on May 25, 1871, asking for restoration of the land the members thought they had purchased in good faith, offering to purchase it if need be (at the original price of $0.50 an acre), and pointing out that the Company had already lost more acres on the south shore through high water levels and erosion than it was asking to have added on the north shore.

Egerton Ryerson delivered the letter and personally explained to the Crown Land commissioner what the Company members believed had caused the error and the difficulties that had resulted. In a letter dated August 1, 1871, he confirmed this discussion:

• • • it is clear that all parties understood that the sale and purchase included all the land and marsh to the Lake and Bay, on all sides of Long Point. This is actually the case in fourteen out of the sixteen "blocks" in which the island of Long Point was divided. But on the north side of Blocks 15 and 16, where the shore of the marsh and sand beach is very crooked, the Surveyor, Mr. Black, (apparently weary of his task and concluding it) did not follow the shore,. . . but he drew a straight line from the south side of the "Gap" at the west end of Long Point Bay to near the limits of "Ryerson's Island," including within Block 16, the whole of the two Rice Bays, but leaving out a few acres of the north shore of Block 15, the northern part of Rice Bay Point, and strips of marsh and sand beach, west of Rice Bay, on the northern shore of Block 16. What is marked on Mr. Black's Map as a small island of reeds on the north side of the mouth of Rice Bay, is now only an exten-sion of Rice Bay Point, consisting of reeds and rice, skirted to some distance into the Bay, on both sides, by rushes, but containing, I believe, not a foot of dry ground on which to erect a tent. It is on these bits of marsh north of Mr. Black's boundary line that certain persons, regardless of right, anchor their large boats, in which they sleep and cook, while, in small skiffs, they poach upon the neighbouring marsh - premises of the purchasers of Long Point to their great annoy-ance, the poachers keeping watch and scudding to their rendezvous whenever they see members or servants of the company approaching.

A later letter to the Office of Crown Lands from J.I. MacKenzie, Com-pany secretary-treasurer, stated even more clearly how lack of the land in question put the Company's plans for safeguarding the Point in jeopardy.

Without an undisputed right to all the territory of Long Point, our property is rendered comparatively of little value, and the money already expended is as good as thrown away; while, on the other hand, it is of no earthly value to the public, it cannot be used for purposes of navigation. It cannot be used for fishing purposes. It can only be used to injure the value of the property belonging to our company, and to serve as a lurking place for poachers.

The government did not respond favourably immediately, but finally, on June 5, 1874, the directors confirmed the purchase of the property "compris-ing 655 acres more or less at a direct cost of $341.85, and a considerable indirect expenditure spread over several years.. • The newly acquired "land" was immediately enclosed by galvanized wire strung along 300 piles set 60 yards apart.

Meanwhile, the problem of fishing rights had been resolved with consider-ably less trouble. All the land, except Ryerson's Island, had been purchased with fishing rights reserved to the government to a considerable, though varying, distance offshore. The government, however, was quite willing to lease the fisheries to the Company; indeed the arranging of a nine-year lease, at $50 per annum, was one of the first acts of Company business concluded on July 17, 1867. The tone of a letter, dated a few days earlier, from John W. Kerr, the local fisheries overseer, suggests he may not have been sorry to turn responsibility for the Long Point waters over to the Company.

• As you proposed to pay fifty Dollars a year for the Fisheries of Long Point surrounding your property and that of the other owners and occupants, I have come to the conclusion to let you have them at that price. I rented one lot to Mr. Edward Fenn [a squatter] on the 12th of February last and when up there on Saturday last, I gave him his license as I was bound to do. Several other applications were made; but these I declined purfuring [sic] your tender. I called on Mr. D. Tisdale of Simcoe on my way up and he very kindly took me in his buggy to your managers. I didn't prosecute Peter Price/or/Maurice Fitzmaurice for violating the game laws. I will however return there again and do so.

Various evidence makes it clear that the Company was fairly generous with its fishing rights, letting licenses to local residents for small-scale commercial fishing. What was prevented was heavy commercial fishing and the use of fishing as a ruse to gain access to illegal hunting.

In less than ten years the foundations of a lasting organization had been established. By 1871 the original membership of seven had expanded to fif-teen, with eight additional men having been granted life licenses to fish and hunt. One steward, three keepers, and nine punters were listed as employees.

In short, Secretary-Treasurer Mackenzie seemed quite justified in writing rather smugly in April 1872:

Long Point for many years before its purchase by the Company, was the terror of shipowners and mariners, on account of the "wreckers" who haunted it. The Company has made arrangements with the marine insurance companies, and shipping associations, to take charge of and protect from wreckers, all ships and property coming ashore there. In striking contrast to the state of society, in and around Long Point, prior to the jurisdiction of our Company, is the condition of matters there now. Six families (the heads of whom are employed by the Com-pany) reside there now in great comfort. Drunkenness and dissipa-tion have been rooted out of the place; and it is from such and their abettors, that the opposition to our rule emanates. The Sabbath is now observed. During the shooting season, as many gentlemen as can be accommodated are invited to shoot, subject to the regulations of the Club.

Another outsider's view of the early days of the Company is equally en-thusiastic. This was a July 1868 sketch by Alexander Somerville, a writer who for several years presented the results of interviews with Canadian entrepreneurs and farmers under the name, "The Whistler at the Plow". Like most of Somerville's pieces, it is sententious and too long to quote here in its entirety. But a few paragraphs give an interesting insight into contemporary opinions of the Company.

A sparse population inhabit the island, the adult males numbering about twenty. They, and lake rovers from the opposite American shore, made havoc of winged game at any season of the year, irrespec-tive of the natural game law, which suggests that birds should not be disturbed when breeding. And muskrats, to which the marshes of wild rice and isolated shores afford sustenance and pleasant places of habitation, were killed for their skins throughout the year. The young, only half-grown, were trapped in the summer and fall. The domes of the muskrat dwellings were penetrated by spears in winter, and the creatures rudely mangled when in their comatose condition .…

The company, on attempting to take possession as proprietors, were opposed by.. twenty men. They, and their fathers before them, had killed wild ducks and muskrats on Long Point - they were not to sur-render their rights at the bidding of strangers. "We do not ask you," rejoined the company, to go away or submit to a loss of any privilege or emolument. We desire you to remain and share with us in the advan-tages of an improved system of operations." These being specified in detail, the men accepted the conditions.

The number of skins obtained by promiscuous hunting in the year before this arrangement was less than 2,000 mink and muskrat, many of them inferior. In 1867, first year after muskrat protection began, the number was 3,053. In 1868, second year of protection, the number was 6,700. In two years more the annual yield of muskrat peltry will be probably 20,000....

The market price [for this year's skins] had not been exactly ascer-tained; but... the head-keeper and a deputation from the twenty assistants had [recently] been in Hamilton and took home with them $1,000. to be divided as a first instalment of this year's emolument. The moral effect of this systematic arrangement is yet more pleasing to contemplate than the augmentation of a commodity of commerce. The skins were formerly bartered at a store for goods, of which whisky was a leading article. Now the trappers receive cash, and purchase their store necessaries for cash. Already they feel themselves rising in the social scale. They and their families are better clothed and the houses have an atmosphere of comfort ....

About this Long Point sporting enterprise there is an aspect of moral improvement which consorts agreeably with the usual vocations of "The Whistler at the Plough."

. . . The Long Point Company are the first [I have] met with who evolve this unique compound product, all by one operation - larger quantities of a useful article for public benefit, higher social life in the working producers, and fun to the share-holders.

The History of the Long Point Company

Photo Courtesy of Norman Ferris

Reconstruction of the history of an organization that has lasted over one hundred years is difficult. There are, of course, the minute books one of them impressively bound in leather. Their terse language, however, leaves a great deal to the imagination, though they do pinpoint major changes in policy. Sometimes old letters, journals, and accounts fill in the gaps and relieve the sterility of the official record books. Just as often, however, they open new conjectures, either from their inexplicable references or from the assumptions of their authors.

In the case of the Long Point Company, one can also draw on two semi-official histories: one printed in Hamilton in 1872, and another written by the Company's managing director in 1932 under the title The Long Point Company. There is also "Recollections", by Edward Harris, Company president from 1886 to 1898, which he wrote in 1918 as a description of the Point and the Company. These are valuable sources, but there is no question that each is coloured both by the character (and experience) of its author and the times in which it was written.

Another problem is that of selectivity. The writers of minute books and even memoirs tend to concentrate on topics that are not necessarily of inter-est today. Critics would find it hard to believe the amount of time and energy these businessmen put into apparent minutiae. Over the years membership increased, as did the various operations that had to be super-vised. Employees had to be found, paid, directed, housed in many cases, fired, pensioned. Buildings had to be erected; then they had to be furnished or repaired after the ravages of time, fire or storms. Members' rates for various services had to be set. Arrangements had to be made for transporta-tion to the Point and for handling various income-producing activities. Dif-ferences between members had to be settled. Above all, sensible regulations for shooting had to be agreed to every year.

The details are endless and not really very interesting to those not directly involved at the time. What is perhaps of more interest and what can be at least sensed from the minute books is the sort of problems that have come up at various times and the influence that certain strong leaders have had on the Company's fortunes.

The founding members consisted of a group of strong-willed individual-ists who had very definite, but at times wildly divergent, views on the methods to be employed in the management and control of the marshes and ridges they now owned. The first president, Thomas Kerr (1866 to 1872), and his successor, S.D. Woodruff (1872 to 1885), clearly ruled with an iron hand, but they depended heavily on attorney David Tisdale and, interest-ingly enough, Egerton Ryerson, who was not actually a member but who came from a local family and whose work in education had given him ex-cellent political connections.

As previously noted, these men faced the problems of finding employees and gaining the cooperation of local residents by hiring local hunter-poachers. They paid them well and respected their skills. The minute books show they expected good work and honest dealings in return. For example, the first manager, Charles Brown, was given a leave of absence in October 1870, partially for reasons of health, but also because the directors were upset by the "scandal arising from reports that he had a woman of ill- repute living with him at The Cottages. A month later he was dismissed but continued to be invited back to hunt occasionally until 1876 when the minutes note (without specifying his offence), "That he will not be allowed to come here and shoot."

Another way in which the Company gained the confidence of the local people was by allowing its employees and others to trap, especially for muskrat, on the Point. The Company sold the pelts, retaining half the receipts as an important source of income. As early as 1870, when the mar-shes were still recovering from having been overhunted, furs totalling about $1278 were taken; the trappers' share of the proceeds was in excess of $600, a considerable sum for those days. (By comparison, in 1954 about 13,000 rats were taken at a value of just under $10,000; the Company received $4,800 as its share of the proceeds.)

At various times employees have also been permitted to shoot ducks when members did not wish to do so, selling any surplus to the members or to a designated local wholesaler at set rates.

Another group of early decisions centred on buildings. Harry's Place was a good spot for getting together but the club required a real and more con-venient headquarters. When Egerton Ryerson deeded Ryerson's Island to the Company, he tried to persuade the members to locate their headquarters on that island. But this was not favourably received. The final location, west of Ryerson's Island on the creek into the marsh, was a compromise and something of a favour to the Port Rowan residents who were being asked to work for the Company.

Harry's shanty was moved over the ice to this location, and a clubhouse with kitchen facilities added. This was replaced in 4875 with a more elaborate headquarters, with rooms for visitors, dining facilities for every-one, and a commodious kitchen not only for the dining room but for the cleaning of birds shot by members and the preparation of lunches to be car-ried by the hunters and their guides. (The big oval tin lunch pails line an upper shelf in the headquarters kitchen to this day.) This building, with fre-quent additions and repairs, served until after the turn of the century. A new one was built then and is still in use.

Over the years buildings were erected for employees expected to live on the Point. Other cabins which various local hunter-squatters had built, in the headquarters area and elsewhere, became the property of the Company; the locals who became employees continued to live in or use them under leases, but the Company took responsibility for repairs. From the earliest minutes through to the present day, there are records of keepers' cabins being built, moved, or repaired; new facilities being installed (for example, an icehouse as early as 1868); and an almost constant discussion of leases.

By 1871 it was also decided that any stock or life-right member could build a lodge in the headquarters area for his exclusive use, but the building would become the property of the Company. Today over thirty buildings make up the headquarters known simply as "The Cottages".

Transport to the Company land was another of the myriad details that had to be looked after. In the very early days members reached The Cot-tages on John Spain's steamer, which also served a mainland hotel. In ~ a local schooner was chartered to do all the Company's boating, and from that time on nearly every year's minutes show that some such local arrange-ment had been made.

The Company also had to settle disagreements among members on occa-sion. The marsh was divided into hunting grounds or "bunches", and only one hunter could hunt in a bunch at any given time. Eventually there were conflicts over this conflicts that led to violent arguments and occasional accidents when two men shot simultaneously.

These conflicts led to a real confrontation around 1880. It was not just petty animosity but rather a show-down between the original promoters and the new members who felt they were being over-ruled too often and that the decisions were being made, not always in the best interests of the club and the Point, but rather to keep this younger, enthusiastic group in place.

Edward Harris, who was to become president in 1885, was an outspoken leader for the latter group, and an argument he had with William Hunter, a respected senior member, sparked the confrontation.

At the time it seemed everyone but Harris understood that a certain bunch was Hunter's preserve. One fine October morning, when ducks were to be found in plenty in every pond in the marsh, Hunter and Harris, with their punter-guides, raced for the same location. What happened next has led to the bunch being known as the "Battleground". As Harris told the story:

Photo courtesy of Jack Reeves

When within about 100 yards of it and about twenty yards ahead, Hunter's punter threw out his decoys not with the intention of shooting there, but to claim the 400-yard limit for the nearest gun. Harris placed his decoys in the proper place notwithstanding. Hunter's punter then lifted his decoys and replaced them in another part of the bunch at a distance of about 100 yards. They shot all day, shot often falling in each boat. Instead of one punt returning with a bag of 100 or over, each boat succeeded in getting from eighteen to twenty birds.

The confrontation in the dining room that evening must have been one to remember for a long time, but Harris apparently, in the long run, had made his point. According to his account:

That evening at dinner was stormy, but it resulted in the framing of Field Rules which placed all members on an equality. Not only that, but there followed an unbroken peace which has continued to this date.

Those Field Rules were original, there being no other shooting club to copy from. In fact, for some years after, the Secretary of the Long Point Company was asked by other clubs in their formation for copies of the Rules….

In those days the "big bag" was a craze. The punter's shooting had no doubt much to do with the early troubles of the Company. Nor is it surprising that they made a vigorous struggle for its continuance. The punter's reputation was made by a return with a boat load of ducks, the greater portion of which he usually claimed fell to his gun.

The field rules as hammered out that evening were then consolidated by a committee made up of Secretary John I. MacKenzie, Edward Harris, James Hewlett, and David Tisdale. At the June 7, 1881 meeting, they submitted and won approval for the following Field By-laws:

I

The shooting on the property of the Long Point Company is limited to Shareholders, holding Five Shares, the representatives of Shareholders, Life License holders and guests.

II

Geese may be killed from and after April first; each member limited to five days, provided that none but members and life members shall shoot geese. Teal and Wood Duck from the first to the eighth of Sep-tember inclusive; all ducks from October first, until the close of the season. One Deer may be killed or more if so regulated at the previous annual meeting, by each owner of five shares; other game may be shot in season. The hours for Duck shooting shall be from eight a.m. until fifteen minutes after sundown.

III

The priority for choice of positions shall be decided daily by ballot, the selection to be availed of within half an hour atter drawinv hy thc member posting to the position chosen with due diligence. No pers~sn shall shoot within four hundred yards of another who has previously located.

IV

A list of shooting locations, sufficient in number for the day, shall be placed in the Club Room every morning before the ballot is taken; such list shall be signed by two of the employees of the Company, who shall, to the best of their ability, place the best location, or stand, first on the list, and so on in order of merit to the bottom of the list.

V

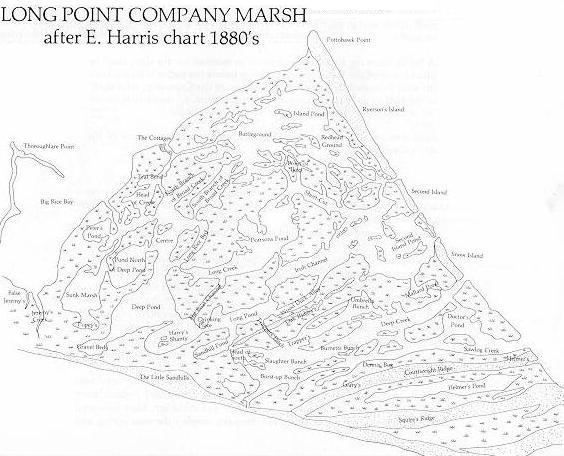

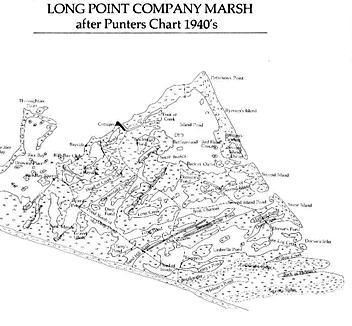

The shooting locations referred to in these field rules were shown on a chart of the big marsh. Edward Harris' descriptions of them are in an appen-dix to this book.

These rules were to be amended later, but their spirit still guides the club today.

The 1881 meeting not only adopted new field rules, but a new approach to management generally. The reassessment was speeded by the fact that a fire had done extensive damage to the hay marsh and the forest cover on three of the ridges, as well as destroying the premises of keeper Andrew Helmer. There was evidence that the fire had gone so far out of control because W. Jackson, an assistant keeper, had left his station. Since Jackson was a favourite of head keeper William Leary, this put Leary's judgment into ques-tion. In addition, Leary's particular hard-drinking, very personal style of management seemed to have outlived its usefulness.

Later that summer a special committee of the board looking into new methods of management met in Hamilton. Both Leary and Helmer were present. Undoubtedly both men knew change was in the air. They informed the committee they planned to leave Company employ the next spring and make new lives for themselves and their families in Manitoba. The directors, grateful for the very great contributions both had made during the tough, formative years of the Company, agreed to do everything in their power to help the two make a fresh start in the West. (Among other things, Colonel Tisdale was able to use his connections to obtain land grants and free transportation west for them.)

Photo courtesy of Lore and Legends

A new, stricter regime began. Alfred March was hired as head keeper; Though he lasted less than a year, his former employment as a game- keeper in England and as a Canadian policeman - was symbolic.

The new management tightened up other hunting matters. l"lew regula-tions were also passed requiring members to do such things as furnish their own lodges and supply their own bedding.

Liquor regulations were tightened, too, though gradually. There is every indication that in the early days of the Company hunters and their employees alike were a hard-drinking lot. Edward Harris has told of visiting President Samuel Woodruff in his cottage and being surprised to find a large bottle labelled "Warner's Safe Cure" on the dining table. "Well," said Harris, "You are the last man I would have suspected of drinking a quack medicine." Woodruff replied, "I never drink any medicine. But if I don't put my whisky in one of those bottles the punters will get it."

Whether or not Woodruff's suspicion of the employees was justified, it is obvious that each of the early punters expected, in fact demanded, a quart of whisky per day as a part of their wages. And many members regarded whisky as the drink to go with the lunches packed daily by the cook for each hunter and his guide. But after a while many members - and even punters came to admit they were not in top form for hunting after even one or two drinks. Members first attempted to set an example by foregoing whisky in the marshes. They then offered the punters an extra fifty cents a day in lieu of the liquor allowance. In time, tea, coffee, or hot soup became the ex-pected replacement at lunchtime. Thus, although the dining room was usually stocked, under various arrangements, with spirits and wine for members' use (but not for sale), Edward Harris was able to say that the notorious Long Point became dry forty years before the rest of Ontario.

Photo courtesy of Long Point Company

Samuel Devoe Woodruff, second President of the Long Point Company (above) and Walker Ferris, Head Keeper

It was also during the 1880s that the Company began to counter poachers less often with persuasion and more often with prosecution in the courts.

During the 1890s Edward Harris persuaded the directors to go into the fishing business themselves. He agreed to acquire the necessary boats, nets, and other gear and served as manager. Although Harris seems to have worked very hard (he even moved to Port Dover) and put a great deal of his own money into the venture, it proved unprofitable. It also proved divisive for the Company since some members even questioned Harris' financial reports, though no doubt of his sincerity and honesty could be found. In 1898 Edward Harris resigned as president of the Company, partially because of this pressure, and the fishery equipment was sold.

By the twentieth century, the poachers were more or less under control and the fisheries were disposed of, but new problems came up. Modern technology raised new questions constantly (as it still does). In -1909 the members outlawed motorboats (though they had considered purchasing one the year before), a rule that was to be changed only in 1954 and then with firm restrictions. Around 1916 an electric generator and a water system were installed, which proved very convenient but, of course, posed their own problems in terms of maintenance and replacement.

The gas and oil companies, in their constant search for new fields, did not ignore Long Point. As early as 1918 the Dominion Natural Gas Company negotiated a ten-year lease with the board; by 1934 it had drilled several wells, three of which were good. By 1942 the Central Pipe Line Company was after leases to drill for both gas and oil, and the Long Point Gas & Oil Company and others soon followed suit. Finally the Company formed its own Pintail Oil & Gas Development Ltd. in 1958. By this means it hoped to protect both the members' interests, if a large strike should be made, and the fragile environment of the Point itself. After British Petroleum was allowed to drill a test well, which proved a very limited success, the members noted that the formation of their own company had been "wise in that the poor results experienced by B.P. would discourage any other attempts by rival companies to base and drill on Long Point."

The world was indeed moving in on the Point, which had been isolated for so long. One new neighbour was the Provincial Parks Department, which, in 1921, established the Long Point Park on land west of the Old Cut. To give greater access to it, the province built a causeway across the eastern side of the Walsingham swamp, linking the park's sandy beaches with the Port Rowan mainland. In 1928 the Company was persuaded to deed 141 acres on its western boundary to enlarge the park.

New neighbours began to appear in summer cottages (many eventually winterized) on the property. In 1944, the Company granted land to Hanson Ferris, its manager and head keeper, for cottage development. This land was expropriated by the government in 1960 and became the Long Point provin-cial park.

Other clubs also began to appear on the Point. This was not a completely new development - the Big Creek Gun Club existed before 1890, and late in the nineteenth century poachers on the Point attempted, unsuccessfully, to avoid prosecution by incorporating themselves as a club. Relationships with the newcomers were somewhat more amicable than they had been with the group under prosecution, though at least one group, the Rice Bay Club, un-doubtedly originated with would-be poachers.

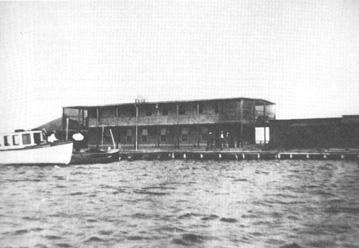

The Rice Bay Club's date of origin is uncertain but its buildings' origins are not. While title to part of the north beach was still in dispute, one of the house boat-scows that plagued the Long Point Company ran aground on that beach and was left marooned there. When the land was finally declared Company property, it demanded a lease from the men, who by now had levelled and built a clubhouse on the derelict scow. These men, professing to negotiate in good faith, failed for a variety of seemingly legitimate reasons to agree to pay the lease fee demanded. They would forget it, not have a quorum, or neglect to bring it up at an annual meeting.

Then, suddenly, in 1920 they demanded title and possession, as more than ten years had elapsed without the Long Point Company evicting them. In other words, they claimed title under a form of squatters' rights. The Com-pany issued a writ against them but did not serve it, fearing that to do so might stir up such hostility as to do more harm than good. (Several Rice Bay Club members were prominent in political circles.) This opinion was strengthened by the fact that the club's members were primarily fishermen and the few who hunted respected the Long Point Company's rights. To cap it all, the government of the day United Farmers of Ontario was known to harbour little love for the rights of corporations over those of the individual.

The litigation was dropped and the Rice Bay Club received title by adverse possession. The Company staked out a one-acre perimeter to the Club buildings and granted an easement of access across its land, which sur-rounded the Club property. The Rice Bay Club caretaker received a year-to- year lease for his garden spot outside that acre.

Something of the same sort of approach was adopted about the Old Cut lighthouse land, which the Crown had expropriated from the Company in 1879. When the Cut was closed entirely and there was no reason to continue the lighthouse, the Department of Marine and Fisheries sold it to a Mr. Han-cock about 1917. The Company was not apprised of the sale until it had been completed. An attempt to prove the government should have turned the land back to the Company brought opposition from Hancock, and, in 1925, the Company withdrew, as the property was on the western boundary of its holdings and posed no threat to hunting.

The Bluffs Shooting and Fishing Club was established in 1919. The Com-pany granted a five-year lease for it to H.H. Collier, of St. Catharines, in return for work he had done in clearing up title to some of the Long Point lands and leases. The lease covered use of the Dr. Salmon Cottage on the bluffs, permission to build a shooting lodge, boat houses, etc, and a permit to take one deer per member per season. This arrangement lasted for some time on an annual lease to Collier, Bruce L. Smith, of Toronto, and A.W. and H.J. Taylor, of St. Catharines. In 1928 rental was increased and the following year the lease was granted to Collier only. He argued that to carry out necessary repairs and to plant wild rice and wild celery throughout the marsh he required a long-term lease, and he eventually got it. In 1931 Collier died. This caused a few problems, but eventually a new lease was drawn up, giving shooting rights (limited to four approved guns) to be used from Nigger Pond east.

Low water levels prompted the use of modern technology for ditching in the big marsh during the 1930s. Even prior to the drought of 1933-34 lower lake levels had disturbed conditions there, and some channels were dug to improve the flow of water. But the drought, combined with other factors, seriously altered existing plant life and water conditions. After taking expert advice and considering several alternatives, the Company purchased a second-hand dredge and began an extensive program of channelling, dyking, and dredging. The work was completed in 1940, though occasional redredging has been necessary since. The dredge had a valuable side effect, too, as the Company discovered it could be rented out at a considerable profit when not in use.

Another project that combined ecological benefits with financial ones was lumbering. This, of course, was an activity which the Company had originally shied away from. When the land was first bought, it carried timber licenses to Colonel Clark and W. Little until 1869. This arrangement never worked very well. As late as 1871 the Company had to buy up their rights and make strict requirements as to when the cut timber would be removed.

Since lumbering had certainly contributed to erosion on the Point, it is not surprising that the subject does not appear again in the minutes until the mid-1930s, except for one or two instances when permission was granted to remove timber from burnt-over land. In the 1930s, however, there was a decision to combine extensive reforestation with selective lumbering. Both were highly successful.

Throughout its history, the Long Point Company has often enjoyed the presence of distinguished visitors. The first was Prince Arthur in 1869. (One amusing note in the minute books is struck by a contemporary motion to grant His Highness "a life license - - to shoot over Long Point - - - subject however to ratification by the shareholders at a general meeting." That ratification was not formally given until 1910, forty-one years later!)

Meanwhile, many other important men came to shoot at Long Point. At eighteen, Prince George, then a midshipman in the British navy, was an enthusiastic guest. So were many of Canada's governors-general the Mar-quis of Lorne, the Marquis of Lansdowne, Lord Stanley of Preston, the Earl of Minto, the Earl of Athlone and, more recently, Viscount Alexander of Tunis and Governor-General Michener. The large, wood-panelled dining room at headquarters has letters of sincere thanks from these and other honoured guests framed and displayed on its walls along with memorabilia, mounted specimens, portraits, and paintings.

Photo courtesy of Almetta Secord

Louis Agassiz Fuertes, the eminent artist and naturalist, spent a week at the Cottages in October 1915. The story is still told of how Fuertes visited the punters' shanty one night with his paper and paints. He suggested he might paint a scene from the marsh, and, as Charlie Reeves described it, all the punters "gathered around and soon everyone was giving him advice. As each suggestion was made, Fuertes would add it as if he had to have the help of the punters." Charlie said, "Finally their interest flagged and they drifted away. No sooner had the last man left than Fuertes began to work seriously at his painting. In about fifteen minutes he had completed it."

The result of that evening's work is the picture entitled "A Record of a Wonderful Week at Long Point, October 21-6, 1915." As Charlie Reeves said, "He knew all along exactly what was needed, and how he was going to do it, to look right."

The problems the Company faces today cannot, perhaps, be regarded as unusual, but they are very real indeed. High lake levels in recent years have destroyed property and changed the shape of the Point. (The south beach can no longer be used by four-wheel-drive vehicles.) Taxes and other costs are becoming a burden. As the general public's use of small craft grows, there is an ever-increasing problem with trespassers. The keepers are in-structed to ignore those whose actions pose no threat to the Point, but at best many are thoughtless litterers, others are positively destructive of the environment.

Much more serious, there is growing public and government pressure to open the land to public use. This upsets many of the members, not primarily because it threatens their private hunting preserve but because they fear open public use would threaten Long Point itself. They respect the aim of the founding members to save the land from destruction by overuse and they fear public access would undo one hundred years of their work.

I believe them to be right. In theory, the Canadian Wildlife Service might be able to manage Long Point as well as the Company. In practice, however, it is doubtful that this would happen. As an absolute owner, the Company is able to instruct its keepers to be as strict as need be against illegal fishing and hunting as well as common trespass. Should a government agency or employee attempt the same control, the worst offenders from among the general public would exert such political pressure that soon the most un-savoury and thoughtless citizenry would be invading the marshes and dunes at all seasons. The resultant harassment of the wild life and destruction of vegetation over the unstable dunes would spell the demise of that fragile and beautiful sandspit as we know it.

Photo courtesy of Harry B. Barrett

Jack Reeves left and the Honourable Roland Michener Govenor General of Canada, enjoying the fruits of Long Point Company's marsh lands.

Photo courtesy of Harry B. Barrett

This breakwall was constructed during a serious highwater period. Here lake water was breaking through the sand spit of Long Point. The Long Point Company laid in rubble in order to break the force momentum of the lake. This operation maintained the control needed to insure the survival of species in the Long Point Company's marsh area, which in turn allowed the company to continue with healthy sport hunting.

THE LAND THAT TIME FORGOT

DUNCAN MCLEOD OCTOBER 11 1958

https://archive.macleans.ca/article/1958/10/11/the-land-that-time-forgot?fbclid=IwAR0WB64UzuhyTBvXOW_-ZdobgxXyqj-PrEUdlnoi_wC9ePA1YjlIeDvCiUw#!&pid=30

This is Long Point: a timeless tangle of swamp and exotic vegetation jutting into Lake Erie. Its inhabitants: animals, birds, reptiles, fishes and periodically multi millionaires

Ninety miles southwest of Toronto there lies a land as wild as when time began. It has no permanent human inhabitants. Its brooding silence is broken only by the restless wash of the surf and the mournful cry of gulls. Pilot blacksnakes six feet long droop like pendants from cottonwood trees; bald eagles perch on butternut trees; below them dwarf deer three feet tall browse on orchids in tiny verdant valleys. Muskrats by the thousand paddle through marshes that reach to the horizon, and where the water deepens into pools, thirty five-pound catfish and hundredpound carp bask lazily. Big black-and-gold wamper snakes slither through stands of waving grass; the soft sand of sweeping beaches is pocked with the tracks of leather shelled turtles. Great flights of wild ducks feed on vast ponds ripe with a golden harvest of wild rice.

This land that time forgot is Long Point, a scimitar-shaped peninsula of sand and marsh that angles twenty-five miles into the eastern end of Lake Erie.

Long Point stayed wild when the surrounding country was tamed largely because nobody had any use for it. It was too desolate for fishermen, who built their villages on the friendlier mainland shore. Farmers avoided its valueless jumble of beach, desert, forest and marsh; hunters came, took their game, and returned to higher ground. In the mid-1800s, when game had been thinned on the mainland, Long Point's teeming wildlife was threatened by a rush of hunters, and for a few years following 1850 there was a carnival of slaughter on the point. This was halted in 1866 when the entire peninsula was sold as a private game preserve to a group of wealthy Canadian and American sportsmen, and the land they bought has survived the intervening ninety odd years unchanged.

The peninsula draws a line almost due east from the mainland into Lake Erie; the southern shore is an unbroken stretch of white sand, most of the northern shore a 33,000 acre marsh. The mainland on this side is a continuation of the marsh; from the base of Long Point it hooks an irregular crescent to the north, then juts south

again in a wedge-shaped promontory called Turkey Point. The basin enclosed by Turkey Point and a spur that runs toward it from Long Point is known locally as the Inner Bay. The bay is really a huge pond—an average of no more than seven feet deep swarming with minute forms of plant and animal life that in turn provide food for a teeming population of fishes: catfish and carp, bowfin, sunfish, rock bass, white bass, suckers, bullheads and channel cats.

This surfeit of fish is the chief source of income for the only community near Long Point, Port Rowan, an unusual village of 750 people on the mainland curve of the Inner Bay. Most of Port Rowan’s able-bodied men are professional hunters who fish the bay, trap the marshes and guide duck hunting parties for their living. Leon Schram, the chubby manager of the Port Rowan fisherman's co-operative, says the Inner Bay supports more fish per acre than any other body of water in North America, and their rich diet makes them outgrow fish of the same species in most other places.

To give every man a fair share of the catch the Inner Bay’s 36,140 acres is surveyed into twenty-three fishing lots; each is the preserve of two, three or four men, who fish their lot on shares. Much of their catch is sold alive. In a year tank trucks with aeration equipment haul about 300,000 pounds of live bullheads, channel cats and catfish to the southern states, and another 200.000-odd pounds of live carp to Toronto, Montreal and Philadelphia, where they are in demand for Jewish New Year celebrations. About 25,000 pounds of rock bass and sunfish are sent in iced cartons to Chicago and Detroit for Chinese buyers, who claim they are the sweetest fish that swim. The Fishermen come by thousands with the total annual catch of all fish is around 650,000 pounds, an extraordinary yield of thirty-five pounds for each acre.

“The bay is filled with millions of small and large mouth bass. This harvest is netted during the spring and fall. Between May and August commercial fishermen are not allowed to set their seines, since the bay is filled with millions of small mouth and large-mouth black bass that come from every part of Lake Erie to spawn and stay to dine. When the bass season opens July first thousands of sporting fishermen come to Long Point. Many of them don’t bring boats, and the Port Rowan fishermen take out parties of ten or twelve who often catch the limit of six bass each in a few hours.

Even in July, when bass fishermen crosshatch the surface of the Inner Bay, Long Point itself is left largely to its wildlife. The bay, to begin with, is treacherous. The shallow basin is roiled by any passing storm, and every year overconfident fishermen are drowned—fourteen in 1955—so that most are reluctant to float too far from safety. Then, too, Eong Point has its own defenses. The marshy shoreline blocks passage for large boats; a small boat can reach the peninsula by passing through an oozing bog swarming with snakes, mosquitoes and deer-flies, but even then it’s impossible to travel far, for the land here is criss-crossed by moatlike marshes and connecting ponds.

The base of the peninsula can he reached by road from the mainland along a tree-lined causeway that passes through a public park studded with six hundred summer cottages. But the causeway ends three miles up the peninsula at a muddy channel; on the other side is an immense bog with signs warning that from here on this is private property. From this point to the lighthouse at the lakeward tip is all Long Point with the exception of a small strip near the eastern end known as the Anderson property—is owned by the millionaires’ duck hunting club that bought the point ninety years ago. While visitors in summer may receive permission to enter their domain, none are permitted during the duck-hunting season.

Even with permission, reaching Long Point’s bog-blocked inner lastnesses isn't easy. While the sandy beach offers a path for anyone with the endurance For a long hike, it is no highway and it can be dangerous. Bill Ainsley, the lighthouse keeper, drives a jeep along the beach to get back and forth between his lonely post and the mainland, but he picks his times carefully; violent southwest gales often crash breakers across the entire width of Long Point.

It’s far from a full gallery, but here are some of the Point’s birds, animals, fish and reptiles...

Behind these natural barriers flourishes a fantastically numerous and variegated animal population. Trappers from Port Rowan take about twenty thousand muskrats every year, and every spring the Port Rowan Lions Club and Canadian Legion branch combine to stage a dinner for hundreds of people from as far away as Toronto who feast on roasted muskrat hindquarters served under the euphemism “marsh hare.”

So many turtles live in the marsh that a visiting naturalist once bubbled unscientifically that they were “dotted all over the place.” There are mud turtles and painted, or pond turtles; fifty-pound snapping turtles, whose shear like jaws can easily amputate a man's finger at one bite; map (or geographic) turtles: pretty yellow-spotted turtles; and malodorous musk turtles.

Frogs, toads and salamanders flourish in the marsh, including the ugly giant salamander, or “mud-puppy,” which has a foot long, dark brown, lizard like body and bushy red gills behind its snout like head. These amphibians feed cranes, herons, bitterns and a teeming snake population. Long Point is a happy hunting ground to herpetologists who come from every part of the continent to gather bagfuls of snakes, but snakes are a constant curse to Mrs. Harvey Ferris, whose husband owns the colonial style Old Cut Inn at the end of the road leading up to Long Point. Her two sons are avid collectors, and she invariably searches their pants' pockets for snakes before dousing them in the washing machine. Until last summer they kept their snakes in a big wooden box; then a storm washed it away. "I often wonder what happened.” mused chunky Harvey Ferris, "if someone found that box and looked in.” Anyone who opened the lid probably would have been terrorized but unharmed. While there are some fearful snakes on Long Point, none is poisonous. The fox snake, or wamper as it is called in Port Rowan, grows as long as six feet and as big around as a man's forearm. It coils when approached, doubles its neck into an S-shaped loop, vibrates its tail so rapidly it buzzes, and strikes with a sharp, short hiss. The tree-climbing pilot blacksnake, just as big but glossy black, will also coil when threatened and hiss fiercely. The brown-and-yellow puff-adder coils its tail, raises its head, spreads its neck flat like a hooded cobra and hisses menacingly when it's approached then opens its mouth wide, goes into convulsions, rolls over ana plays dead. But like many ham actors it overplays its part, if it's turned right side up, it will stubbornly roll over again.

Side by side with the reptiles, Long Point harbors a myriad of animals raccoons, skunks, rabbits, woodchucks, weasels, minks, wolves and dwarf deer. Jack Allan, Fish and Wildlife Officer at Port Rowan, says he has seen full grown deer "no bigger than jack rabbits.” Biologists believe the deer have multiplied beyond the food supply adequate for normal growth.

The air teems as richly with life as the ground. The great horned owl, yellow-billed cuckoo, hairy woodpecker, ruby-throated hummingbird, king-bird, crested fly-catcher, Baltimore oriole, bronzed grackle, red-eyed vireo, northern bald eagle, marsh hawk, spotted sandpiper, Florida gallinulc, wood duck and black duck all thrive on the peninsula.

In the spring and fall Long Point is one of the most important half-way resting stations on the continent for migrating birds: the white-breasted nuthatch, thrush, plover, sand-piper, knot dowitcher, horned grebe, snowy owl, black billed cuckoo, towhee, indigo bunting, purple martin and almost every type of wild duck in central North America. Birdwatchers travel hundred of miles to spy on them. The high point of the birdwatching calendar is in March when thousands of whistling swans sweep down on Long Point, followed by as many as two thousand birdwatchers.

The whistling swans bypass Long Point in the autumn, frightened off by the blasts of shotguns fired by hundreds of duck hunters. Traveled hunters say Long Point is one of the best duck-hunting grounds in the world, and to Port Rowan ducks are big business. Nearly all the village men are hired as guides by the private clubs during the duck shooting season; they also rent boats, decoys and blinds along the Bay outside the clubs’ properties to sportsmen out for a day’s shooting.

Any duck hunter with a glance to spare for the vegetation can eye one of the few flower sanctuaries left in North America. Monroe Landon, a big-boned farmer-naturalist in the nearby city of Simcoc, who has spent much of the past forty odd years studying Long Point's llora and fauna, says "there are literally acres and acres of pink orchids as well as masses of lady slippers, Indian paint plants and bladderwort.” Landon has identified nearly 1,400 species of vascular plants growing wiki on the Point, and remarks sadly that all these once grew in equal abundance throughout southern Ontario.

Except for brief bouts of exploitation, Long Point has lain largely untouched since the first United Empire Loyalists arrived in 1794. An early settler, Samuel Ryerson, wrote in later years that “he would go to the woods for his deer like the farmer would go to the fold for his sheep.” By 1830 most game had been shot off on the mainland, and scows filled with American “sports" began to come across the lake to Long Point for a lost weekend and easy hunting. By 1850 there was a carnival of wholesale slaughter on the Point. American cities offered an insatiable market for game and professional hunters shot animals throughout the year. Soon only the ducks were left.

The government of Canada West—as Ontario was then known — was understandably annoyed at having Long Point’s animals massacred by Americans, and tried to sell the peninsula at public auction in 1857 and again in I860: there were no bids. In 1866 it was put up for sale again; this time it was sold for nineteen thousand dollars to a group of duckshooting sportsmen who formed the Long Point Company. They received a charter from the Legislative Council and Assembly of Canada West to make Long Point a private hunting preserve.

This outraged the professional hunters, who had built shacks on Long Point and claimed squatters’ rights, and a long comic-opera war between free-booting hunters and Long Point's owners began, stained by the blood of thousands of birds and one man. This is the story as it’s told in Port Rowan: to secure a clear deed from the squatting hunters the Company persuaded most of them to sell, but had to give them life rights to shoot on Long Point. The Company built a lodge, each member had a cottage built, a ferry was purchased to reach the camp, and punt channels were dredged into some of Long Point’s ponds. By the time the club members finally got around to hunting, they found that the professional hunters shot most of the ducks; they knew the marsh and were skilled in placing decoys. Fighting back, the businessmen arranged free transportation to the duck-rich prairies, and free grants of land there, for the hunters. With their competitors removed, the businessmen hired non - professional hunters from Port Rowan as guides.

But their troubles weren't over yet. They had to permit the Port Rowan guides to shoot too, and the new guides in their turn shot most of the ducks. This time the club members tried bribing the guides not to shoot by adding a quart of whisky to their day’s wages; the guides became drunk as lords before going into the marsh, with disastrous results to the members’ sport. They withheld the whisky until noon. This saved the morning’s shooting, and to rescue the afternoon’s sport they began to cut down the whisky ration.

The first guide to have his ration cut was named Shootly Franklin. When noon came Franklin brought out the lunch pail, pulled out a soda water bottle, took out the cork, smelled it, and cried: “My God, has it come to this?”

Fearing the guides might quit in disgust, the members decided to indoctrinate them with more respect for temperance and their employers. They outlawed Sunday shooting, laid up the ferry to the mainland on Saturday night, and invited the guides to sumptuous dinners at the lodge. After dinner an honorary member, Rev. Egerton Ryerson, preached on the advantages of a temperate Christian life. His eloquence and the members’ goodfellowship converted the guides into repentant sinners and faithful employees.

“The private detective was found with a shotgun wound in his forehead”

The company needed them. As ducks became scarcer in the mainland’s marshes new professional hunters from Port Rowan began to poach the company’s land. The sportsmen made game wardens of their guides, but the poachers placed pillow slips with eyelets over their heads to prevent being identified. Feelings rose so high that several times members were fired at by the “whitecaps,” as the poachers came to be known. When the poachers began to shoot the deer the company had imported to re-stock Long Point, the members hired John Allan, a private detective from London, Ont., who promised to make examples of the culprits. Two days later a warden stumbled across Allan’s body, a shotgun blast in his forehead, a dead deer and a discharged gun lying beside him.

Alian obviously had been murdered, in spite of the clumsy attempts to indicate he had shot himself accidentally there were no powder burns on his face and the murderer was never brought to trial. With the threat of the gallows hanging over their heads, the poachers stayed off the company’s property.

But between their poaching and members' shooting, ducks had become wary of Long Point. The older club members determined to protect their investment from newer members like J. T. Lord, an Englishman who boasted of having shot 3,300 ducks in one season. They ruled shooting would be from nine to four, no more than fourteen guns would be allowed in the marsh at one time, and each member could bag only five hundred ducks a season—at a time when Canada’s game laws placed no restrictions on shooting ducks. Lord then bought another share in the company, believing he now had the right to shoot a thousand ducks. The members told him the number of shares he owned had nothing to do with the limit, and Lord had to abide by the by-laws.

The company planted wild rice in the ponds and rarely shot in them. Each year more ducks returned; by 1910 the company’s marshes were again filled with birds. Today each potential member has to agree to obey the by laws which are stricter than present Canadian game laws and be personally acceptable to other members, pay about five thousand dollars for a share and about fifteen hundred dollars a year toward the club’s maintenances and operating expenses.

For these reasons the members are usually multimillionaires. The nine current American members are Junius S. Morgan and Henry S. Morgan, New York City, directors, J. P. Morgan and Co.; John Hay Whitney, NYC, financier; Robert Winthrop (and his brother Frederic), director, The National City Bank of New York; F. Trubee Davison, NYC, trustee of the Mutual Life Insurance Co.; George T. Bowdoin, NYC, banker: Paul C. Cabot, Boston, director, J. P. Morgan and Co.; John T. Pratt. Jr., NYC, broker. The Canadians are R. S. McLaughlin, Oshawa, chairman of the board of General Motors of Canada; Arthur L. Bishop, Toronto, president. Consumers’ Gas Co.; Major-General Harry F. G. Lctson, Ottawa, director, Powell River Co.; W. C. Harris, Toronto, president, Harris and Partners and R. A. Laidlaw, director of the R. Laidlaw Lumber Co.

In spite of its multitudes of ducks the company is no longer bothered by poachers from Port Rowan. Without Long Point’s marshes to attract ducks, and a few hunters in it to chase some out to neighboring marshes and the bay, the villagers wouldn’t have jobs as guides with other clubs or as suppliers to visiting sportsmen.

"An aura of tragedy"

Yet to many people in Port Rowan, Long Point is a place of mystery. Few ever go there and strange stories and legends are told of the Point. One of the strangest concerns a chest of gold sovereigns which the captain of an English pay-ship, HMS Mohawk, is said to have buried beneath a beech tree on Long Point in the War of 1812 to prevent its capture by an American fleet. The only object numerous searchers have dug up is an old cast-iron kettle, and by now it is difficult to know where to dig someone dug up the only beech tree on Long Point.

Long Point also has an aura of haunting tragedy. Ever since ships sailed the upper lakes the treacherous shoals off the south shoreline have been claiming ships. Many of their crews perished in the pounding surf and were buried by the drifting sand. Beachcombers have often stumbled on eerie sights. In December, 1880, six seamen were found huddled behind a dune, frozen stiff. Above them, in an eerie vigil of death, a youth sat on the dune under a tree, staring out over the lake. In December, 1909, nine frozen sailors were found sitting upright in a steel lifeboat grounded on a shoal, their hands gripping motionless oars.

There are brighter tales of Long Point, too. One of the best revolves around a wamper snake, a species with an occasional inclination to sleep with people, particularly in the fall when the nights become chilly. This has led to many disquieting nights among duck hunters. Mrs. Pearl Wrighton, for one, will never forget the night she slept with a wamper. She, her husband and two children were sleeping in separate bunks in a Long Point shooting cabin; a strange ticking noise kept her awake all night while her family slept. In the morning her husband got up and said: “Come on, Pearl, let’s have some breakfast.”

“Oh Will,” she moaned, "I couldn’t sleep all night. You make your own breakfast and let me sleep."

Glancing curiously at her, he said in a low voice: “Come on. Pearl, get up."

"No,” she said firmly.

“For God's sake Pearl,” he shouted, “get out of that bed.”

There was terror in his voice. She leaped. Turning around she saw a sixfoot wamper contentedly coiled above her pillow.

Fishermen later told her the peculiar ticking she heard was the snake's scales rhythmically moving as it breathed. They also said it was easy to tell when a wamper was around; it smelled like a cucumber.

Twenty years ago wampers were common near Port Rowan, but now they’re scarce. Many have been killed and the survivors have taken refuge on Long Point. Even here their days—and the days of many more animals on Long Point—may be numbered. Wallace B. Nesbitt, MP for Oxford, Ontario, is advocating that the Long Point peninsula be developed as a public park project.

To Monroe Landon, the naturalist who has tramped the point for forty years, this is a desecration. "If a road were built up this peninsula to enable people to see Long Point,” Landon says, “it would end forever the isolation which has made it such a wonderful sanctuary for animals. It should be left the way it is, a land that time and man have passed by.” Jç

Back to Harry"B"

Design by: